Topic: - Archetypal inductive and deductive theory

Name: - Upadhyay Devangana S.

Sub: - Literary Theory & Criticism

Paper: - 07

Std: - M.A. Sem – 2

Roll No: - 07

Submitted to: - M.K. Bhavnager University

Frye gained international fame with his first

book, Fearful Symmetry (1947), which led to the

reinterpretation of the poetry of William Blake. His lasting

reputation rests principally on the theory of literary criticism that he

developed in Anatomy of Criticism (1957), one of

the most important works of literary theory published in the twentieth century.

The American critic Harold Bloom commented at

the time of its publication that Anatomy established Frye as

"the foremost living student of Western literature." Frye's

contributions to cultural and social criticism spanned a long career during

which he earned widespread recognition and received many honours.

Born in Sherbrooke, Quebec but raised in Moncton, New Brunswick, Frye was the third

child of Herman Edward Frye and of Catherine Maud Howard. His much older

brother, Howard, died in World War I; he also had a sister, Vera. Frye

went to Toronto to compete in a national typing contest in 1929. He

studied for his undergraduate degree at Victoria, where he edited the college literary

journal, Acts Victoriana. He then studied theology at Emmanuel College (like Victoria College, a constituent

part of the University of Toronto). After a brief stint as a student minister

in Saskatchewan, he was ordained to

the ministry of the United Church of Canada. He then studied at Merton College, Oxford, before returning to Victoria

College, where he spent the remainder of his professional career.

As A. C. Hamilton

outlines in Northrop Frye: Anatomy of his Criticism, Frye's

assumption of coherence for literary criticism carries important implications.

Firstly and most fundamentally, it presupposes that literary criticism is a

discipline in its own right, independent of literature. Claiming with John Stuart Mill that "the

artist . . . is not heard but overheard," Frye insists that

The axiom of criticism must

be, not that the poet does not know what he is talking about, but that he

cannot talk about what he knows. To defend the right of criticism to exist at

all, therefore, is to assume that criticism is a structure of thought and

knowledge existing in its own right, with some measure of independence from the

art it deals with (Anatomy 5).This "declaration of

independence" (Hart xv) is necessarily a measured one for Frye. For

coherence requires that the autonomy of criticism, the need to eradicate its

conception as "a parasitic form of literary expression . . . a second-hand

imitation of creative power" (Anatomy 3), sits in dynamic

tension with the need to establish integrity for it as a discipline. For Frye,

this kind of coherent, critical integrity involves claiming a body of knowledge

for criticism that, while independent of literature, is yet constrained by it:

"If criticism exists," he declares, "it must be an examination

of literature in terms of a conceptual framework derivable from an inductive

survey of the literary field" itself

In literary criticism the term

archetype denotes recurrent narratives designs, patterns of action character –

types, theme, and images which are identifiable in a wide variety of works of

literature, as well as in myths, dreams, and even social rituals. Such

recurrent items are held to be the result of element and universal forms or

patterns in the human psyche, whose effective embodiment in a literary work

evokes a profound response from the attentive reader, because he or she shares

the psychic archetypes expressed by the author, An important antecedent of the

literary theory of the archetype was the treatment of myth by a group of

comparative anthropologists at Cambridge University, especially James. Frazer, who’s

“The Golden Bough” (1890 – 1915) identified elemental patterns of myth and

ritual that, claimed recur in the legends and ceremonials of diverse and far –

flung cultures and religions. An even more important antecedent was the depth

psychology of Carl G. Jung (1875 – 1961) who applied the term “archetype“to

what he called” primordial images “, the “psychic residue” of repeated patterns

of experience in our very ancient ancestors which he maintained survive in the “collective

unconscious “of the human race and are expressed in myths, religion, dream, and

private fantasies, as well as in works of literature.

Archetypal literary criticism is a type of critical theory that interprets

a text by focusing on recurring myths and archetypes (from the Greek archē,

or beginning, and typos, or imprint) in the narrative, symbols, images, and character types in literary work. As a form of literary criticism,

it dates back to 1934 when Maud Bodkin published Archetypal Patterns

in Poetry.

Archetypal literary criticism’s

origins are rooted in two other academic disciplines, social anthropology and psychoanalysis; each contributed to

literary criticism in separate ways, with the latter being a sub-branch of

critical theory. Archetypal criticism was at its most popular in the 1940s and

1950s, largely due to the work of Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye. Though archetypal literary criticism is no longer

widely practiced, nor have there been any major developments in the field, it

still has a place in the tradition of literary studies

In The Golden

Bough Frazer identifies with shared practices and mythological beliefs

between primitive religions and modern religions. Frazer argues that the

death-rebirth myth is present in almost all cultural mythologies, and is acted

out in terms of growing seasons and vegetation. The myth is symbolized by the

death (i.e. final harvest) and rebirth (i.e. spring) of the god of vegetation.

As an example, Frazer cites the Greek myth of Persephone, who was taken to the Underworld by Hades.

Her mother Demeter, the goddess of the

harvest, was so sad that she struck the world with fall and winter. While in

the underworld Persephone ate 6 of the 12

pomegranate seeds given to her by Hades. Because of what she ate, she was forced to spend half the year, from

then on, in the underworld, representative of

autumn and winter, or the death in the death-rebirth myth. The other half of

the year Persephone was permitted to be in the mortal realm with Demeter, which

represents spring and summer, or the rebirth in the death-rebirth myth.

Bodkin’s Archetypal

Patterns in Poetry, the first work on the subject of archetypal literary

criticism, applies Jung’s theories about the collective unconscious,

archetypes, and primordial images to literature. It was not until the work of

the Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye that archetypal

criticism was theorized in purely literary terms. The major work of Frye’s to

deal with archetypes is Anatomy of Criticism but his essay

“The Archetypes of Literature” is a precursor to the book. Frye’s thesis in

“The Archetypes of Literature” remains largely unchanged in Anatomy of

Criticism. Frye’s work helped displace New Criticism as the major

mode of analyzing literary texts, before giving way to structuralism and semiotics.

Frye’s work breaks from both Frazer and Jung in such a way that it is

distinct from its anthropological and psychoanalytical precursors.

In his remarkable and

influential book Anatomy of Criticism N. Frye developed the archetypal approach

and the practice of literary criticism.

There are two basic

categories in Frye’s framework, i.e. comedic and tragic. Each category is

further subdivided into two categories: Comedy and romance for the comedic:

tragedy and satire for the tragic. Though he is dismissive of Frazer, Frye uses

the seasons in his archetypal scheme. Each season is aligned with a literary

genre: comedy with spring romance with summer, tragedy with autumn and satire

with winter.

·

Comedy is aligned with spring because the genre of comedy

is characterized by the birth of the hero, revival and resurrection. Also

spring symbolizes the defeat of winter and darkness.

·

Romance and summer are paired together because summer is

the culmination of life in the seasonal calendar, and the romance genre culminates

with some sort of triumph, usually a marriage.

·

Autumn is the dying stage of the seasonal calendar, which

parallels the tragedy genre because it is known for the “fall” or demise of the

protagonist.

·

Satire is metonymies with winter on the grounds that

satire is a “dark” genre. Satire is a disillusioned and mocking from of the

three other genres. It is noted for its darkness dissolution, the return of

chaos and the defeat of the heroic figure.

The context of a genre determines how a symbol or image is to be

interpreted. Frye outline five different sphere in his schema: human, animal,

vegetation, mineral, and water.

·

The comedic human world is representative of wish –

fulfillment and being community centered. In contrast, the tragic human world

is of isolation, tyranny, and the fallen hero.

·

Animal in the comedic genres are docile and pastoral

(e.g. sheep), while animal are predatory and hunters in the tragic 9e.g.

wolves)

·

For the realm of vegetation the comedic is, again,

pastoral but also represented by gardens, parks, rose and lotuses. As for the

tragic, vegetation is of a wild forest, or as being barren.

·

Cities temples, or precious stones represent the comedic

mineral realm. The tragic mineral realm is noted for being a desert, ruins, or

“of sinister geometrical images”.

·

Lastly the water realm is represented by rivers in the

comedic. With the tragic, the seas, and especially floods, signify the water

sphere.

Frye admits that his

schema in “The Archrtypes of Literature” is simplistic, but makes room for

exception by noting that there are neutral archetypes. The example he cites are

islands such as Circe’s which cannot be categorized under the tragic or

comedic.

·

Definition of Inductive theory:-

“The philosophical definition of inductive reasoning is

much more nuanced than simple progression from particular/individual instances

to broader generalizations. Rather, the premises of an inductive logical argument indicate some

degree of support (inductive probability) for the conclusion but do not entail it; that is, they suggest truth

but do not ensure it. In this manner, there is the possibility of moving from

general statements to individual instances (for example, statistical

syllogisms, discussed below).

Though many dictionaries define inductive reasoning as

reasoning that derives general principles from specific observations, this

usage is outdated.”

·

Definition of deductive theory

Deductive

reasoning happens when a researcher works from the more general information to

the more specific. Sometimes this is called the “top-down” approach because the

researcher starts at the top with a very broad spectrum of information and they

work their way down to a specific conclusion. For instance, a researcher might

begin with a theory about his or her topic of interest. From there, he or she

would narrow that down into more specific hypotheses that can be tested. The

hypotheses are then narrowed down even further when observations are collected

to test the hypotheses. This ultimately leads the researcher to be able to test

the hypotheses with specific data, leading to a confirmation (or not) of the

original theory and arriving at a conclusion.

Developing an inductive, or grounded, theory generally follows the

following steps:

·

Research design: Define your research questions and the

main concepts and variables involved.

·

Data collection: Collect data for your study using any of

the various methods (field research, interviews, surveys, etc.)

·

Data ordering: Arrange your data chronologically to

facilitate easier data analysis and examination of processes.

·

Data analysis: Analyze your data using methods of your

choosing to look for patterns, connections, and significant findings.

·

Theory construction: Using the patterns and findings from

your data analysis, develop a theory about what you discovered.

·

Literature comparison: Compare your emerging theory with

the existing literature. Are there conflicting frameworks, similar frameworks,

etc.?

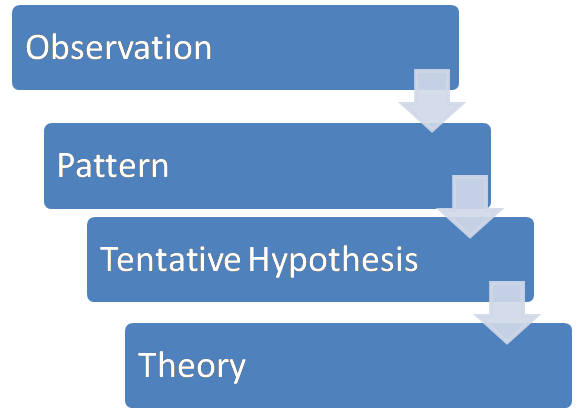

Deductive reasoning works

from the more general to the more specific. Sometimes this is informally called

a "top-down" approach. We might begin with thinking up a theory

about our topic of interest. We then narrow that down into more specific

hypotheses that we can test. We narrow down even further when we

collect observations to address the hypotheses. This

ultimately leads us to be able to test the hypotheses with specific data --

a confirmation (or not) of our original theories. Let it see

through the chart.

Inductive theory is the reveres process of this. In inductive theory

Conformation come first then Observation, Hypothesis and Theory. This theory

also known as “Bottom – up” approach.

These two methods of

reasoning have a very different "feel" to them when you're conducting

research. Inductive reasoning, by its very nature, is more open-ended and

exploratory, especially at the beginning. Deductive reasoning is more narrow in

nature and is concerned with testing or confirming hypotheses. Even though a

particular study may look like it's purely deductive (e.g., an experiment

designed to test the hypothesized effects of some treatment on some outcome),

most social research involves both inductive and deductive reasoning processes

at some time in the project. In fact, it doesn't take a rocket scientist to see

that we could assemble the two graphs above into a single circular one that

continually cycles from theories down to observations and back up again to

theories. Even in the most constrained experiment, the researchers may observe

patterns in the data that lead them to develop new theories.

Deduction: In the process of

deduction, you begin with some statements, called 'premises', that are assumed

to be true, you then determine what else would have to be true if the premises

are true. For example, you can begin by assuming that God exists, and is good,

and then determine what would logically follow from such an assumption. You can

begin by assuming that if you think, then you must exist, and work from there.

In mathematics you can begin with some axioms and then determine what you can

prove to be true given those axioms. With deduction you can provide absolute

proof of your conclusions, given that your premises are correct. The

premises themselves, however, remain unproven and unprovable, they must be

accepted on face value, or by faith, or for the purpose of exploration.

Induction: In the process of

induction, you begin with some data, and then determine what general

conclusion(s) can logically be derived from those data. In other words, you

determine what theory or theories could explain the data. For example, you note

that the probability of becoming schizophrenic is greatly increased if at least

one parent is schizophrenic, and from that you conclude that schizophrenia may

be inherited. That is certainly a reasonable hypothesis given the data. Note,

however, that induction does not prove that the theory is correct. There are

often alternative theories that are also supported by the data. For example,

the behavior of the schizophrenic parent may cause the child to be

schizophrenic, not the genes. What is important in induction is that the theory

does indeed offer a logical explanation of the data. To conclude that the

parents have no effect on the schizophrenia of the children is not supportable

given the data, and would not be a logical conclusion.

Comparison of two reasoning:-

Properties of Deduction

- In

a valid deductive argument, all of the content of the conclusion is

present, at least implicitly, in the premises. Deduction is nonampliative.

- If

the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. Valid deduction is

necessarily truth preserving.

- If

new premises are added to a valid deductive argument (and none of its

premises are changed or deleted) the argument remains valid.

- Deduction

is erosion-proof.

- Deductive

validity is an all-or-nothing matter; validity does not come in degrees.

An argument is totally valid, or it is invalid.

Properties of Induction

- Induction

is ampliative. The conclusion of an inductive argument has content that

goes beyond the content of its premises.

- A

correct inductive argument may have true premises and a false conclusion.

Induction is not necessarily truth preserving.

- New

premises may completely undermine a strong inductive argument. Induction

is not erosion-proof.

- Inductive

arguments come in different degrees of strength. In some inductions, the

premises support the conclusions more strongly than in others.

mate, I will be analyzing a literary piece (single literary piece only) using the archetypal approach. Aside from determining the archetypes and discussing them, what conclusion can I draw to from these archetypes?

ReplyDelete